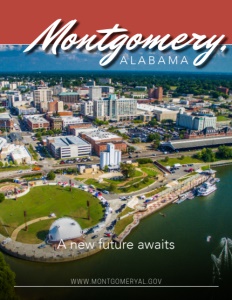

Montgomery, Alabama

A new future awaits

Business View Magazine interviews representatives from Montgomery, AL, as part of our focus on best practices of American towns and cities.

Montgomery is the capital city of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County. Named for Richard Montgomery, a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War, the city of 200,000 is located beside the Alabama River, in the south-central part of the state.

Steeped in history, Montgomery was first incorporated in 1819, became the state capital in 1846, and the first capital of the Confederate States of America in 1861, before the seat of government moved to Richmond, Virginia that same year. In the middle of the 20th century, the city was a major center of the events and protests in the Civil Rights Movement, including the Montgomery Bus Boycott and the Selma to Montgomery marches.

In this new century, after years of deterioration, Montgomery has become nationally recognized for its downtown revitalization and new urbanism projects. “Like a lot of mid-size cities in the country, Montgomery went through a downtown decline in the 1970s and ‘80s, when a lot of our major department stores left the urban core,” explains Lois Cortell, the city’s Senior Development Manager. “By the early 2000s, though, the civic and business leaders were sparking a turnaround with major public, catalytic investments like our Riverwalk Amphitheater, our Riverwalk Baseball Stadium, and our Riverfront Park. And those major investments sparked our downtown’s rebirth.”

“But what’s key now, in 2020, it’s no longer about the public dollars,” Cortell continues. “We are pretty clear that there is privately-driven revitalization and redevelopment occurring downtown. From Jan. 2014 – Dec. 2019, we had more than $195 million of private construction value in our downtown. The City of Montgomery is about 163 square miles, but downtown is only 1.9; so, we’re only one percent of the city. But downtown saw 15 percent of the $1.3 billion of permitted construction value. That’s not land; no soft costs; no professional services; no FF&E (furniture, fixtures, and equipment) – that’s just pure, self-reported construction values.”

As the construction boom in Montgomery continues, Cortell says the city remains focused on creating public projects so that its citizens and visitors, and not just businesses, can participate in its revitalization. One major project that it took on, and an example of its commitment to best practices, was the establishment of the Lower Dexter Park, a small pocket park and memorial to civil rights activist, Rosa Parks, located on Dexter Avenue, a thoroughfare that Cortell calls Montgomery’s “grand boulevard.”

“It starts at our historic, cast-iron, Court Square Fountain and it connects to the State Capitol,” she relates. “And this little segment is one of the most historic in the country; it’s the last five–block leg of the Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights Trail.” The 54-mile-long, Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail was established by Congress in 1996 to commemorate the events, people, and route of the 1965 Voting Rights March in Alabama. “The Court Square fountain was one of the largest markets for enslaved people,” Cortell adds. “It also has the bank which housed the telegraph that gave the orders to fire on Ft. Sumter, which began the Civil War. And it also happens to be the bus stop where Rosa Parks got on the bus and started the historic Montgomery Bus Boycott. It’s all right there on Dexter Avenue in that very small block area, and that’s where this park is located.”

The specific location of Lower Dexter Park is on the former site of the Montgomery Fair Department Store – 29 Dexter Avenue. “The store opened in 1909,” Cortell notes. “It was 146,000 square feet; a huge four-story building, with frontages on Court St., Monroe St., and Dexter Avenue. In the 1940s and ‘50s it was part of a bustling downtown. In the ‘40s, an Art Deco façade got put on – a bright white and blue vitrolite tile, which was a very specialized tile that’s not made in the U.S. anymore. So, it was very distinctive, architecturally. The store closed in the late ‘60s and caught on fire in ’84. That’s when the historic movement to designate Court Square and Dexter Avenue as an historic district of the National Park Service began. The City of Montgomery purchased what was left of that building, along with about a dozen other properties on Lower Dexter that were boarded up at that time, and we started selling those to private redevelopers.”

However, Cortell shares that there were problems getting the adjacent buildings redeveloped because they were built side by side. “When you try to do mixed-use, you need to conform to modern international building codes that require multiple means of egress,” she explains. “And they were just too close together. So, we needed that area to become an egress for the adjacent buildings, which we had just sold for renovation and redevelopment. We were trying to figure that out; we were thinking we could keep the front of the building and take down the back, where it had burned. But we didn’t want to tear down the building and have the urban fabric broken. We hired an architect and we started doing community outreach. We gathered a group of historians and we explained the problem with egress and why the adjacent buildings couldn’t get redeveloped.”

During one of the public meetings, Mary Ann Neeley, a local historian, prevailed upon the city to save what it could of the old department’s store façade, citing its historic value as the place where Rosa Parks had worked as a seamstress, and from where she left work on Dec. 1, 1955, to walk three blocks down to Court Square and wait at the bus stop before climbing aboard and refusing to give up her seat in the front of the bus, thus sparking the long, modern struggle for African-American civil rights.

“So, that was a key,” Cortell remembers. “There were many moments where it would have been cheaper to take it all down and fill it in, but we planned ahead and carefully deconstructed that façade so that we could salvage all those tiles and glass blocks that aren’t made anymore. We were able to salvage a large percentage of those vitrolite tiles and 80 of 114 of the glass blocks. So, the new park is a free-standing façade with four tiers holding it up, three stories high, without touching the adjacent buildings. We kept the fabric of the urban pedestrian environment and ended up with this 1940s Art Deco façade, right next to an 1850s Victorian style and the 1929 Kress Building, a neo-classical building. So, we have this block that’s an eclectic mix of architectural styles that are seemingly disparate, but they end up displaying the broad range that happened here on Dexter Avenue and make up what Montgomery is today.”

The re-building of the historic façade and Lower Dexter Park cost the city nearly $700,000 for its planning, design, and execution. And it was a collaborative project from the outset. In addition to working with local architects, engineers, contractors, and city staff, the team included local historians, the Rosa Parks Museum, Alabama State Archives, the Downtown Business Association, the Downtown Neighborhood Association, and community volunteers.

In addition to providing a new public space, on each side of the park, there has been renewed renovation. Next door at 25 Dexter Avenue, $600,000 has been invested in three apartment units and an antique store that opens into the park, and on the other side, at the Kress Building at 39 Dexter Avenue, $19 million has been invested in 33 residential units and more than 30,000 square feet of commercial space. The project, which was designed by Chambless King Architects and constructed by Liberty Construction, has also raised the bar for public space design in the state and beyond, having won the Alabama APA’s Franklin M. Setzer Outstanding Urban Design Award in 2018.

Not only does Lower Dexter Park keep the rhythm and scale of architecture along the street, it allows Montgomery to re-interpret its own history, celebrating the story and role of Rosa Parks in a way that directly shapes people’s experience of the city, its civic life, and contemporary culture. The Park has already helped spur new civic events such as the Lower Dexter Cruise-Ins – a first Friday street party with classic and muscle cars, food trucks, and music. As the park continues to evolve, as its native grasses and perennial plants mature, public art added, and more events take place, Lower Dexter Park place will define a new era in Alabama history in which people come together to share the city’s present and its dreams of the future.

Another local attraction, the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum, under the auspices of the Equal Justice Initiative, has added to the new life of downtown Montgomery, bringing a huge influx of visitor and tourists to the city. “The Equal Justice Initiative had been in Montgomery for 30 years, but flying low until 2017,” Cortell recounts. “The city sold them some property, and in April, 2018, they opened the National Memorial for Peace and Justice and the Legacy Museum. In 2018, they had 300,000 visitors and since the end of 2019, they’ve had 650,000 people visit.”

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, informally known as the National Lynching Memorial, is a national memorial to commemorate the victims of lynching in the United States, and is intended to acknowledge past racial terrorism and advocate for social justice in America. The related Legacy Museum: From Enslavement to Mass Incarceration, opened on the same six-acre complex near the former market site in Montgomery where enslaved African Americans were sold. The development and construction of the memorial complex cost an estimated $20 million – all raised from private foundations.

Pointing to the new construction downtown, the opening of Lower Dexter Park and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice, as well as a brand new statue of Rosa Parks in Court Square, Cortell is enthusiastic about the prospects of this storied southern city, as it enters the next phase of its long and colorful history. “Montgomery’s future is bright,” she exudes. “People are coming to visit and we don’t expect that to slow down.”

Montgomery is also a city that believes in energy conservation. It has partnered with Cenergistic, a conservation and sustainability consulting firm to help it reduce its electricity consumption, thus lowering costs to it taxpayers, while being more efficient and environmentally-conscious. Over the last three years, it has implemented conservation procedures at several municipal facilities and properties including City Hall, its library branches, the municipal court building, the Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts, Riverwalk Stadium, and the Montgomery Zoo. Before implementing the program, the City spent approximately $3 million in utility costs at buildings targeted by the program, each year. The energy conservation program is projected to save $2.9 million in five years and should cut expected energy costs by more than 20 percent.

“We’re working smarter, not harder, and doing more with less, thanks to technology to better serve our residents and create new opportunities for economic development,” states Public Relations Specialist, Griffith Waller. “The city just won an award for urban infrastructure and digital transformation called the Smart 50 Award from U.S. Ignite of the Smart Cities Connect organization. The two programs that we entered were two of our Smart City programs. One was called Star Watch, where the Montgomery Police Department instituted a new police community technology initiative built around a real-time crime center comprised of camera feeds across the city. The feeds are voluntarily shared by residents and businesses with the MPD so that we can have a safer community and create a force-multiplier effect for our MPD staff.

“Another thing this award recognized was the rollout of LED lighting systems. We worked with Alabama Power Company to upgrade more than 22,000 street lights in Montgomery from the mercury vapor, metal halide, and high pressure sodium bulbs to new energy-efficient LED systems at no cost to the taxpayers. We anticipate saving at least $600,000 in energy costs in the next five years. The most important thing about this is that we’re cultivating a climate where businesses can succeed, residents are happy, and we have a high quality of life for Montgomery.”

AT A GLANCE

WHO: Montgomery, Alabama

WHAT: A city of 200,000

WHERE: In Montgomery County in south-central Alabama

WEBSITE: www.montgomeryal.gov